The fastest human in the world, according to the Ancient Greek legend, was the heroine Atalanta. Although she was a famous huntress who joined Jason and the Argonauts in the search for the golden fleece, she was most renowned for the one avenue in which she surpassed all other humans: her speed. While many boasted of how swift or fleet-footed they were, Atalanta outdid them all. No one possessed the capabilities to defeat her in a fair footrace. According to legend, she refused to be wed unless a potential suitor could outrace her, and remained unwed for a very long time. Arguably, if not for the intervention of the Goddess Aphrodite, she would have avoided marriage for the entirety of her life.

Aside from her running exploits, Atalanta was also the inspiration for the first of many similar paradoxes put forth by the ancient philosopher Zeno of Elea about how motion, logically, should be impossible. The argument goes something like this:

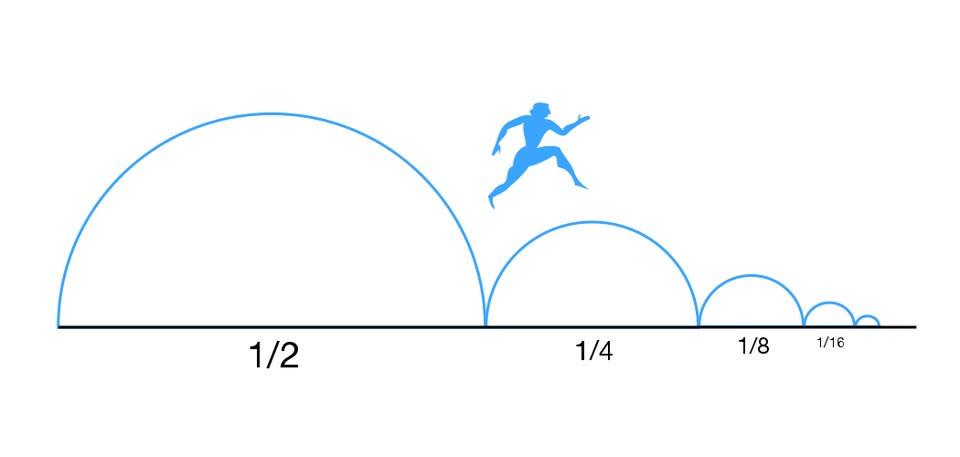

- To go from her starting point to her destination, Atalanta must first travel half of the total distance.

- To travel the remaining distance, she must first travel half of what’s left over.

- No matter how small a distance is still left, she must travel half of it, and then half of what’s still remaining, and so on, ad infinitum.

- With an infinite number of steps required to get there, clearly she can never complete the journey.

- And hence, Zeno states, motion is impossible: Zeno’s paradox.

While there are many variants to this paradox, this is the closest version to the original that survives. Although it may be obvious what the solution is — that motion is indeed possible — it’s physics, not merely mathematics alone, that allows us to see how this paradox gets resolved.

Credit: Pierre Lepautre/Jebulon of Wikimedia Commons

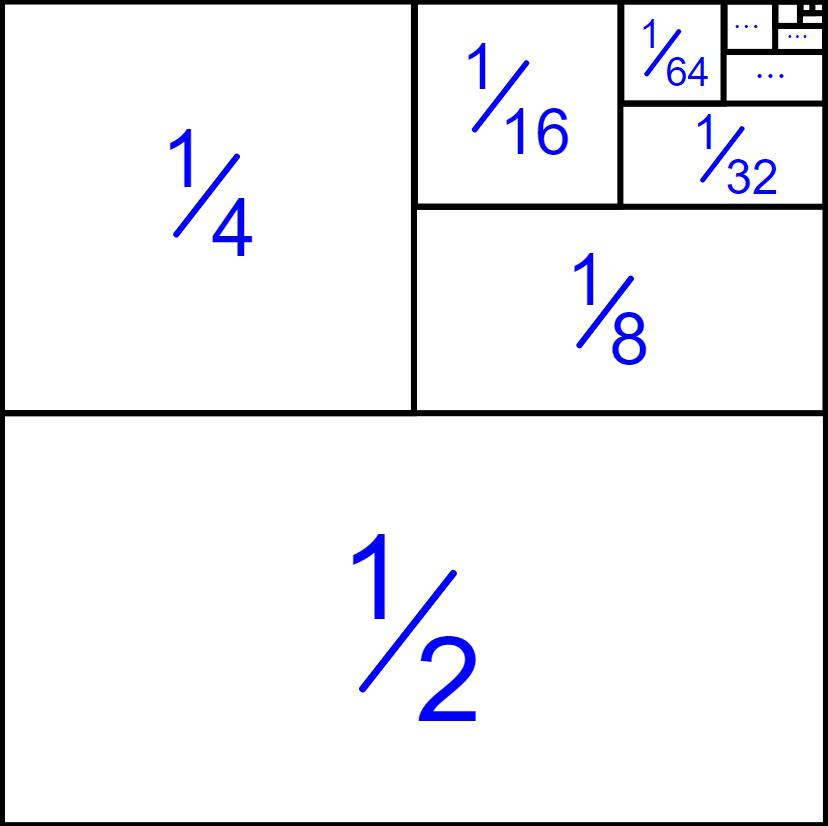

The oldest “solution” to the paradox was put forth based on a purely mathematical perspective. The claim admits that, sure, there might be an infinite number of jumps that you’d need to take, but each new jump gets smaller and smaller than the previous one. Therefore, as long as you could demonstrate that the total sum of every jump you need to take adds up to a finite value, it doesn’t matter how many chunks you divide it into.

For example, if the total journey is defined to be 1 unit (whatever that unit is), then you could get there by adding half after half after half, etc. The series ½ + ¼ + ⅛ + … does indeed converge to 1, so that you eventually cover the entire needed distance if you add an infinite number of terms. You can prove this, cleverly, by subtracting the entire series from double the entire series as follows:

- (series) = ½ + ¼ + ⅛ + …

- 2 * (series) = 1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛ + …

- therefore, [2 * (series) – (series)] = 1 + (½ + ¼ + ⅛ + …) – (½ + ¼ + ⅛ + …) = 1.

That seems like a simple, straightforward, and compelling, solution, doesn’t it?

Credit: Public Domain

Unfortunately, this “solution” only works if you make certain assumptions about other aspects of the problem that are never explicitly stated. This mathematical line of reasoning is only good enough to robustly show that the total distance Atalanta must travel converges to a finite value, even if it takes her an infinite number of “steps” or “halves” to get there. It doesn’t tell you anything about how long it takes her to reach her destination, or to take that potentially infinite number of steps (or halves) to get there. Unless you make additional assumptions about time, you can’t solve Zeno’s paradox by appealing to the finite distance aspect of the problem.

How is it possible that time could come into play and ruin what appears to be a mathematically elegant and compelling “solution” to Zeno’s paradox?

Because there’s no guarantee that each of the infinite number of jumps you need to take — even to cover a finite distance — occurs in a finite amount of time. If each jump took the same amount of time, for example, regardless of the distance traveled, it would take an infinite amount of time to cover whatever tiny fraction-of-the-journey remains. Under this line of thinking, it might still be impossible for Atalanta to reach her destination.

Many thinkers, both ancient and contemporary, tried to resolve this paradox by invoking the idea of time. One attempt was made a few centuries after Zeno by the legendary mathematician Archimedes, who argued the following.

- It must take less time to complete a smaller distance jump than it does to complete a larger distance jump.

- And therefore, if you travel a finite distance, it must take you only a finite amount of time.

- If that’s true, then Atalanta must finally, eventually reach her destination, and thus, her journey will be complete.

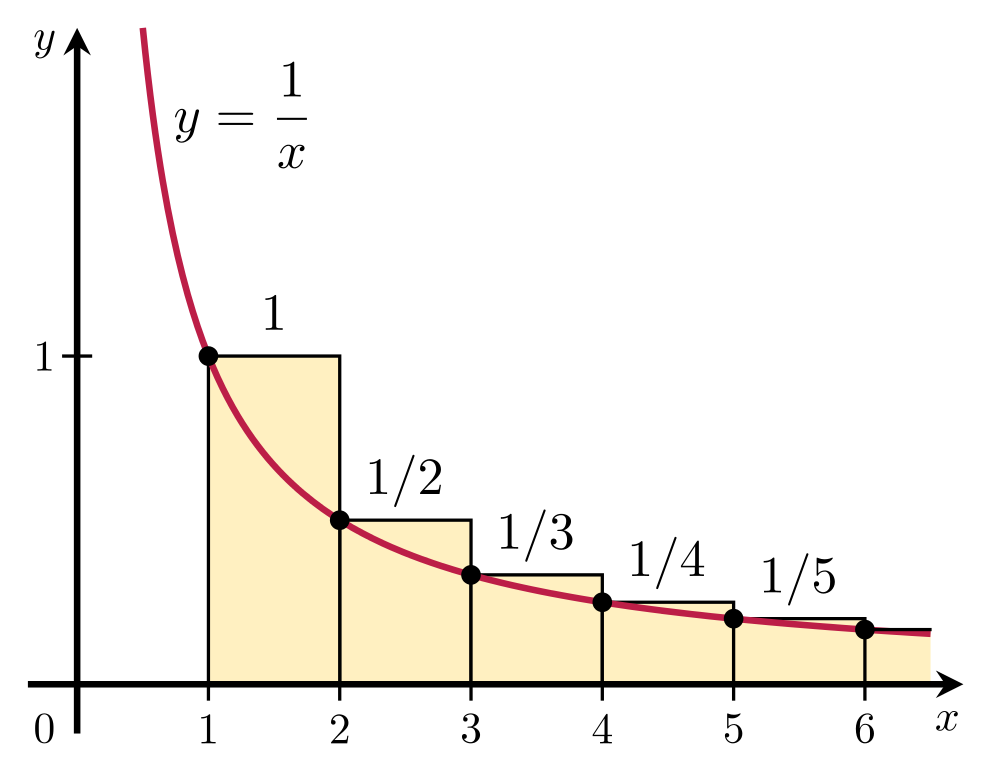

Only, this line of thinking is not necessarily mathematically airtight either. It’s eminently possible that the time it takes to finish each step will still go down: half the original time for the first step, a third of the original time for the next step, a quarter of the original time for the subsequent step, then a fifth of the original time, and so on. However, if that’s the way your “step duration” decreases, then the total journey will actually wind up taking an infinite amount of time. You can check this for yourself by trying to find what the series [½ + ⅓ + ¼ + ⅕ + ⅙ + …] sums to. As it turns out, the limit does not exist: this is a diverging series, and the sum tends toward infinity.

Credit: Public Domain

It might seem counterintuitive, but even though Zeno’s paradox was initially conceived as a purely mathematical problem, pure mathematics alone cannot solve it. Mathematics is the most useful tool we have for performing quantitative analysis of any type, but without an understanding of how travel works in our physical reality, it won’t provide a satisfactory solution to the paradox. The reason is simple: the paradox isn’t simply about dividing a finite thing up into an infinite number of parts, but rather about the inherently physical concept of a rate, and specifically of the rate of traversing a distance over a duration of time.

That’s why it’s a bit misleading to hear Zeno’s paradox: the paradox is usually posed in terms of distances alone, when it’s really about motion, which is about the amount of distance covered in a specific amount of time. The Greeks had a word for this concept — τάχος — which is where we get modern words like “tachometer” or even “tachyon” from, and it literally means the swiftness of something. To someone like Zeno, however, the concept of τάχος, which most closely equates to velocity, was only known in a qualitative sense. To connect the explicit relationship between distance and velocity, there must be a physical link at some level, and there indeed is: through time.

Credit: Gordon Vigurs/English Wikipedia

Because we’re not bound by the qualitative thought patterns that would’ve come along with the mention of the word τάχος here in the 21st century, we can simply think about a variety of terms that we are familiar with.

- How fast does something move? That’s what its speed is.

- What happens if you don’t just ask how fast it’s moving, but if you add in which direction it’s moving in? Then that speed suddenly becomes a velocity: a speed plus a direction.

- And what’s the quantitative definition of velocity, as it relates to distance and time? It’s the overall change in distance divided by the overall change in time.

This makes velocity an example of a concept known as a rate: the amount that one quantity (distance) changes dependent on how another quantity (time) changes as well. You can have a constant velocity (without any acceleration) or you can have a velocity that evolves with time (with either positive or negative acceleration). You can have an instantaneous velocity (i.e., where you measure your velocity at one specific moment in time) or an average velocity (i.e., your velocity over a certain interval, whether a part or the entirety of a journey).

However, if something is in constant motion, then the relationship between distance, velocity, and time becomes very simple: the distance you traverse is simply your velocity multiplied by the time you spend in motion. (Distance = velocity * time.)

Credit: Public Domain

This is how we arrive at the first correct resolution of the classical “Zeno’s paradox” as commonly stated. The reason that objects can move from one location to another (i.e., travel a finite distance) in a finite amount of time is not because their velocities are not only always finite, but because they do not change in time unless acted upon by an outside force: a statement equivalent to Newton’s first law of motion. If you consider a person like Atalanta, who moves at a constant speed, you’ll find that she can cover any distance you choose in a specific amount of time: a time prescribed by the equation that relates distance to velocity, time = distance/velocity.

While this isn’t necessarily the most common form that we encounter Newton’s first law in (e.g., objects at rest remain at rest and objects in motion remain in constant motion unless acted on by an outside force), it very much arises from Newton’s principles when applied to the special case of constant motion. If you consider the total distance you need to travel and then halve the distance that you’re traveling, it will take you only half the time to traverse it as it would to traverse the full distance. To travel (½ + ¼ + ⅛ + …) the total distance you’re trying to cover, it takes you (½ + ¼ + ⅛ + …) the total amount of time to do so. And this works for any distance, no matter how arbitrarily tiny, you seek to cover.

Credit: John D. Norton/University of Pittsburgh

For anyone interested in the physical world, this should be enough to resolve Zeno’s paradox. It works whether space (and time) is continuous or discrete; it works at both a classical level and a quantum level; it doesn’t rely on philosophical or logical assumptions. For objects that move in this Universe, simple Newtonian physics is completely sufficient to solve Zeno’s paradox.

But, as with most things in our classical Universe, if you go down to the quantum level, an entirely new paradox can emerge, known as the quantum Zeno effect. Certain physical phenomena only happen due to the quantum properties of matter and energy, like quantum tunneling through a thin and solid barrier, or the radioactive decay of an unstable atomic nucleus. In order to go from one quantum state to another, your quantum system needs to behave like a wave: with a wavefunction that spreads out over time.

Eventually, the wavefunction will have spread out sufficiently so that there will be a non-zero probability of winding up in a lower-energy quantum state. This is how you can wind up occupying a more energetically favorable state even when there isn’t a classical path that allows you to get there: through the process of quantum tunneling.

Credit: J. Liang, L. Zhu & L.V. Wang, 2018, Light: Science & Applications

Remarkably, there’s a way to inhibit quantum tunneling, and in the most extreme scenario, to prevent it from occurring at all. All you need to do is this: just observe and/or measure the system you’re monitoring before the wavefunction can sufficiently spread out so that it overlaps with a lower-energy state it can occupy. Most physicists are keen to refer to this type of interaction as “collapsing the wavefunction,” as you’re basically causing whatever quantum system you’re measuring to act “particle-like” instead of “wave-like.” But a wavefunction collapse is just one interpretation of what’s happening, and the phenomenon of quantum tunneling is real regardless of your chosen interpretation of quantum physics.

Another — perhaps more general — way of looking at the quantum version of Zeno’s paradox is that you’re restricting the possible quantum states your system can be in through the act of observation and/or measurement. If you make this measurement too close in time to your prior measurement, there will be an infinitesimal (or even a zero) probability of tunneling into your desired state. If you keep your quantum system interacting with the environment, you can suppress the inherently quantum effects, leaving you with only the classical outcomes as possibilities: effectively forbidding quantum tunneling from occurring.

Credit: Yuvalr/Wikimedia Commons

The key takeaway is this: motion from one place to another is possible, and the reason it’s possible is because of the explicit physical relationship between distance, velocity, and time. With those relationships in hand — i.e., that the distance you traverse is your velocity multiplied by the duration of time you’re in motion — we can learn exactly how motion occurs in a quantitative sense. Yes, in order to cover the full distance from one location to another, you have to first cover half that distance, then half the remaining distance, then half of what’s left, etc., which would take an infinite number of “halving” steps before you actually reach your destination.

But the time it takes to take each “next step” also halves with respect to each prior step, so motion over a finite distance always takes a finite amount of time for any object in motion. Even today, the Zeno’s paradox puzzle still remains an interesting exercise for mathematicians and philosophers. Not only is the solution reliant on physics, but physicists have even extended it to quantum phenomena, where a new quantum Zeno effect — not a paradox, but a suppression of purely quantum effects — emerges.

For motion, its possibility, and how it occurs in our physical reality, mathematics alone is not enough to arrive at a satisfactory resolution. As in all scientific fields, only the Universe itself can actually be the final arbiter for how reality behaves. Thanks to physics, Zeno’s original paradox gets resolved, and now we can all finally understand exactly how.

A version of this article was first published in February of 2022. It was updated in January of 2026.

This article Zeno’s Paradox resolved by physics, not by math alone is featured on Big Think.