MetroCards were phased out of New York City’s subways and buses by New Year's Eve in favor of OMNY’s tap-and-go payment system, but there’s still one place the plastic fare card is welcome.

The New York Transit Museum is celebrating the slim taxicab-colored icon with a special exhibition, FAREwell, MetroCard, on view until spring, emphasizing the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) innovations and lengthy collaboration with the arts.

“This is a bit unusual. We don’t typically do exhibits for something extant in this subway,” Transit Museum curator Jodi Shapiro told Hyperallergic. “But the MetroCard represented a huge technological leap in our transit system, and we felt we should bring it to the fore and tell people about it.”

The subterranean Downtown Brooklyn institution’s collection of antique rail cars, trolleys, and buses has long drawn transit enthusiasts interested in stepping into different eras of the city’s history and learning about its mobility.

Location scouts can’t resist the museum’s historic trains and intact Court Street station, which remains connected to the city’s subway system. The 1974 thriller The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, and its Denzel Washington-featured remake, were filmed there, as well as Carlito’s Way (1993).

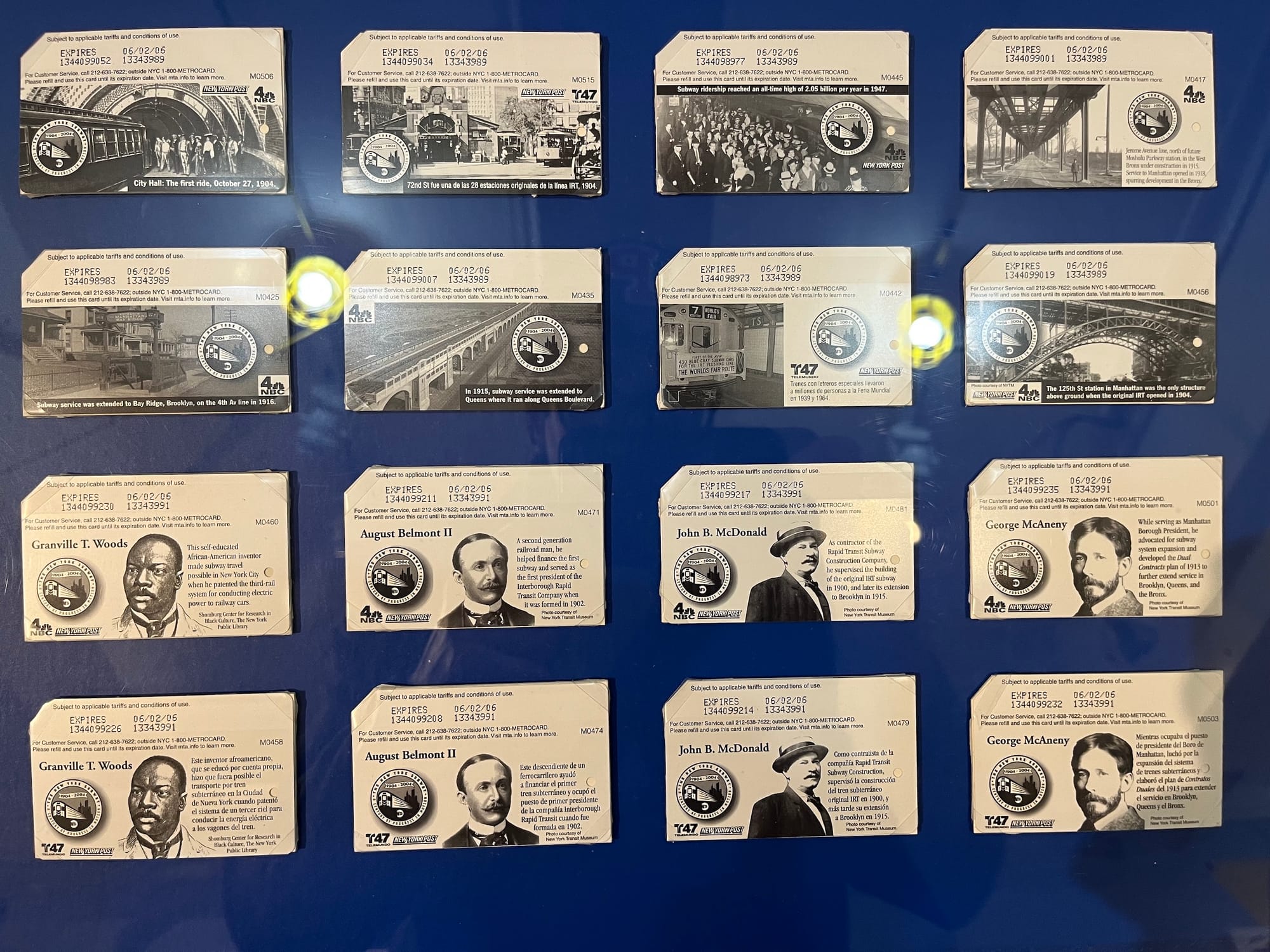

As Al Pacino’s Carlito Brigante frantically fled mafioso heavies through the subway’s distinctive 1960s-era “Redbird” cars, the MTA launched a prototype of the bendable credit card-sized fare card that would replace almost a century of subway tokens. By January 1994, the first MetroCards, which were colored blue with yellow lettering, were introduced to the public. (Several early iterations, including the first collector’s limited edition sell sheet and a pilot brochure, as well as the first yellow cards, are included in the exhibition.)

It wasn’t a small task. Magnetic strip storage cards weren’t yet widely used in the United States, but they had been in operation in Paris and San Francisco for several years. Turnstiles and fare boxes had to be electrified to read the strip that contained the cash value people added instead of purchasing a handful of coin-like tokens. A new revenue facility was built to encode MetroCards and process transactions, replacing its antiquated money room on 370 Jay Street.

“This was all technology that didn’t exist before the MetroCard was chosen,” Shapiro said. “It was one of the biggest technological leaps in the subway’s history.”

People also needed to know how to use the new cards, so the MTA developed a marketing campaign to teach New Yorkers how to add cash, check their balances, and swipe them through card readers at station entrances.

They even created Cardvaark — a furry, tech-savvy cartoon who looks a bit like the geeky older brother of TV’s Arthur, to patrol Times Square and help people get into the subway. But the transit agency pulled the plug on the campaign and he never became a public figure (Cardvaark merch is currently on order for its gift shop).

“I love Cardvaark. I don’t make any secret of it,” Shapiro said. “He would have been a great mascot.”

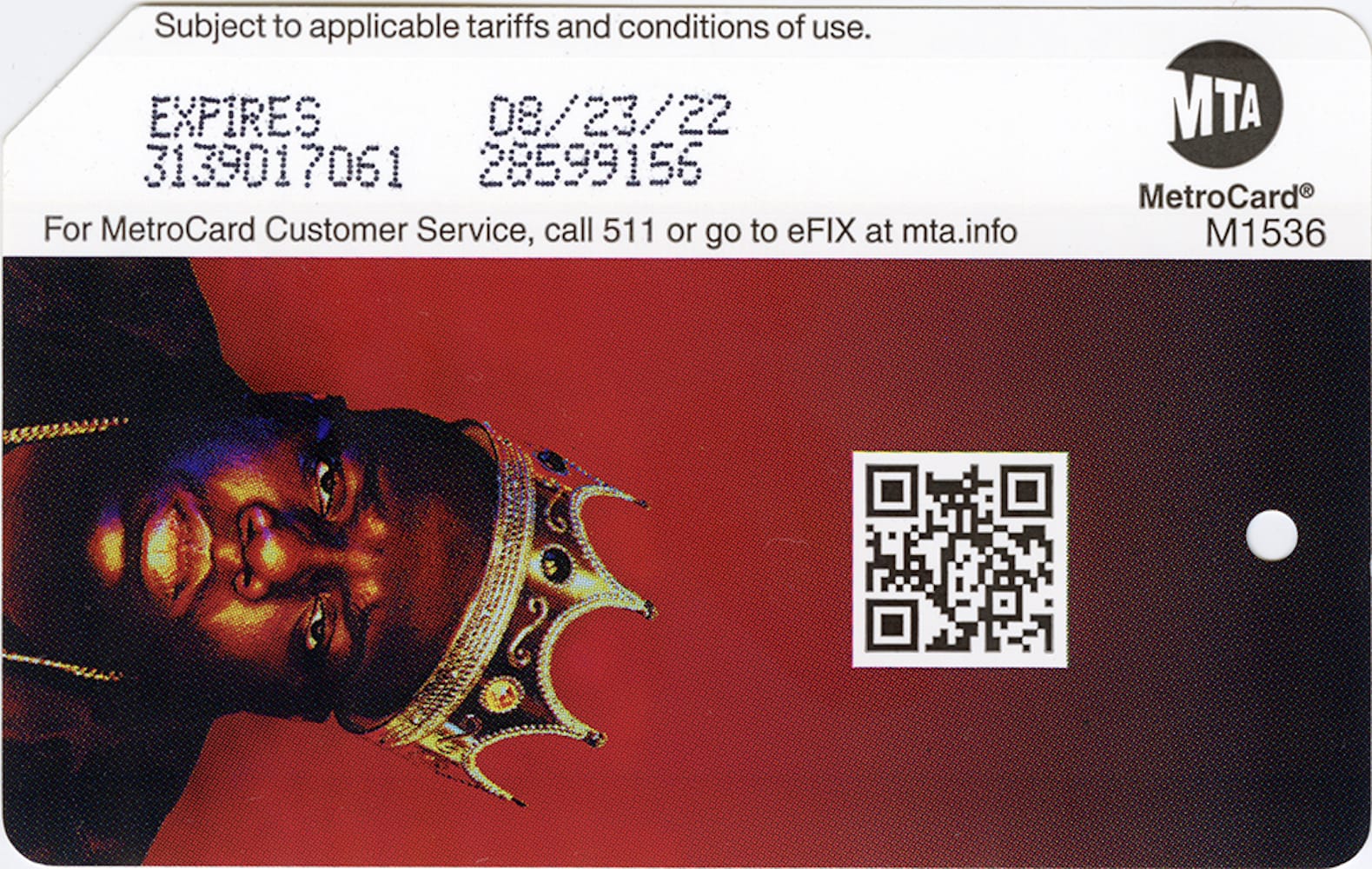

Over the years, the MetroCard has also become a blank canvas promoting the city’s museums, anniversaries, and sports heroes. The Stanley Cup-winning New York Rangers and World Series-winning New York Yankees both earned placement on special editions of the card, but so did the hip hop duo Gang Starr and Spin City, the first TV show depicted on the card. More frequently, the back included safety messages to stay away from the platform edge and offer your seat to riders with disabilities, or even verses from the MTA’s Poetry in Motion design campaign.

Tributes to the MetroCard extend beyond the walls of the Transit Museum. As the beloved card was phased out, local artist Danielle de Jesus began sharing a week-long “miniseries” of her intricately hand-painted MetroCards, featuring designs like a flock of pigeons eating pizza or a bodega storefront.

While some mourn their disappearance, the cards’ replacement is another leap forward. OMNY’s open-loop system accepts contactless credit cards, smartphones synced up to Apple or Google Pay, and wearable devices, eliminating the need to carry American cash and enter the subway system. There’s also a physical OMNY card for people who are used to carrying a separate card just for transit purchases.

“I can’t see them not continuing that type of promotion of the arts and poetry on the OMNY card,” Shapiro said.